In the final episode of Amazon Prime’s Fallout TV series, the heads of five mega-corporations gather to discuss the end of the world.

In a scene reminiscent of the war room scene in Dr. Strangelove, Barb Howard of Vault-Tec presents her vision of the apocalypse to executives from Rob-Co, Wes-Tek, Big MT, and Repconn—a corporate conspiracy ensuring total monopoly over the future through nuclear annihilation of the competition, succinctly defined by Vault-Tec’s Bud Askins as “every other human who isn’t us.” This would allow Vault-Tec and its co-conspirators to initiate various human experiments in the vaults, competing to produce the ideal humans and technologies to rebuild society in the wasteland.

Vault-Tec’s logic struck me as ridiculous. What’s the point of destroying the competition if it will also destroy all resources on earth, and most of your consumers? How does Vault-Tec expect to get rich off the apocalypse, when money may not even be a concept anymore? And what good is money in the apocalypse anyway? Who would even be left to buy the technologies you produce using human experiments? Am I thinking too hard about the logic of a Corporate Big Bad?

The scenario made me think of the famous quote attributed to both Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek: “It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

I first encountered that quote in Mark Fisher’s now nearly 20-year-old book Capitalist Realism, in which he explored the widespread idea that there is no alternative to capitalism. According to Fisher, it is becoming increasingly impossible to even imagine alternatives to capitalism as “business ontology” – the language and logic of markets – colonizes every aspect of life, even our own minds, and becomes naturalized as “human nature.”

He also explores the concept of “hauntology” and lost futures—the idea that philosophies of the past continue to haunt the present.

The Fallout franchise provides a rich text upon which to project Fisher’s ideas (to keep the scope of this essay somewhat contained, I’m going to stick mostly with the TV series). Fallout’s zany wasteland, and the characters who populate its retro-futurist graveyard, contain many parallels to our current post-modern condition.

We may already be living in our own wasteland – we just don’t know it yet.

In the TV show, we see glimpses of the pre-apocalypse world through the eyes of Western movie star Cooper Howard—later to become the Ghoul. The show presents an alternate 1960s in which a bankrupt U.S. is fighting a forever war against vague communists, and has outsourced its contingency planning to a private multinational corporation: Vault-Tec.

We later learn from scientist Lee Moldaver that the company acquired and embargoed her research into “cold fusion” technology, a source of infinite energy that would effectively end the resource war the U.S. is embroiled in (one immediately thinks of the foreign wars in oil-rich countries that our universe’s U.S. always finds itself in, hiding the materialism of its goals with ideological language). However, since Vault-Tec relies on the constant threat of nuclear holocaust to sell its products and fill its vaults, it must suppress the knowledge of cold fusion.

The pre-bomb world combines the nostalgic aesthetics of romanticized 1960s culture with signs of late capitalism. David Elias Aviles Espinoza of the University of Sydney neatly summarized Marxist literary critic Fredric Jameson’s definition of late capitalism as “characterized by a globalized, post-industrial economy, where everything – not just material resources and products but also immaterial dimensions, such as the arts and lifestyle activities – becomes commodified and consumable.”

Cooper himself has become a product—his wife, Barb, convinced him to become a paid spokesman for Vault-Tec, cashing in his all-American cowboy image to sell spots in vaults.

In a scene in episode six, Cooper has a conversation with fellow Hollywood actor Sebastian Leslie at an afterparty for Cooper’s latest Vault-Tec ad shoot. Leslie noted that RobCo bought the Hollywood studio that owned the rights to his character, hinting at the consolidation that comes with late capitalism. Leslie also sold the rights to his own voice to the robot company – literally commodifying himself.

“The future, my friend, is a product,” he tells Cooper. “You’re a product. I’m a product. The end of the world is a product.”

The scene foreshadows the near future, when vault dwellers will become both consumers and products of Vault-Tec. It also parallels our current late capitalist media landscape, where celebrities and influencers exist merely to sell products, not to produce art.

The notion of a “personal brand” is rampant even amongst us normies – to survive in our post-industrial society, we must not only sell our skills, but also ourselves – or a carefully curated and easily consumable pseudo-self. Like the vault dwellers, we are already the products of major tech companies like Google and Meta, which harvest or data, use it for research, and sell it – and it is becoming increasingly difficult to opt out of these ubiquitous technologies.

At the same party scene in episode six, Vault-Tec executives worry in the background over peace negotiations cutting into the company’s profits. The company’s prime directive of perpetual growth is all that matters—it has no duty to the U.S. government or public safety, only a fiduciary responsibility to its investors. However, constant expansion in a world with waning resources is obviously impossible.

In Capitalist Realism, Fisher describes climate change as an “unrepresentable void” for capitalist culture. “Climate change and the threat of resource-depletion are not being repressed so much as incorporated into advertising and marketing,” he writes. “What this treatment of environmental catastrophe illustrates is the fantasy structure on which capitalist realism depends a presupposition that resources are infinite, that the earth itself is merely a husk which capital can at a certain point slough off like a used skin, and that any problem can be solved by the market …”

This is exactly the capitalist realist fantasy to which Vault-Tec subscribes. It uses the threat of environmental catastrophe as material for its ads and marketing, while secretly planning to literally “slough off” the surface and all its inhabitants, then somehow rebuild the world using market forces to solve all of humanity’s problems. Fisher noted that capital’s need for constant expansion means that “far from being the only viable political economic system, capitalism is in fact primed to destroy the entire human environment.”

This is exactly what happens in Fallout. Faced with waning sales, the company ends its final boom-and-bust cycle with a literal bang (technically it’s not yet confirmed that Vault-Tec actually dropped the bombs, but it is heavily implied they at least played a role).

In the pre-War world of Fallout, the fact the U.S. is fighting against communists implies “actually existing socialism” still exists in the world. In the wasteland that develops over the next 200 years (any coincidence this is approximately the age of the U.S.?), themes of capitals realism come into even starker relief. Rather than making way for an entirely new way of life, free from capitalism, the wasteland’s inhabitants find themselves trapped by the structures of the past.

In many ways, the wasteland appears as the conservative apocalypse fantasy, reinforcing capitalist realism—total chaos, every man for himself individuality, people running around with guns killing each other for resources, forming paramilitary factions, etc.

The behavior of the surface dwellers is foreshadowed in the first scene of the show. Cooper and his daughter, Janey, are working a kid’s cowboy-themed birthday party after the implied downfall of Cooper’s career. During the party, the bombs drop. As Cooper scoops up his daughter and runs, he passes a previously genteel suburban dad physically attacking another man in a desperate attempt to get into his bomb shelter.

This is a common trope in TV and movies – the idea that “real” human nature is violent, selfish, and brutal, and our “true” natures will emerge when under extreme stress – this is despite evidence that hunter-gatherer societies value egalitarianism, cooperation, altruism, and peace, according to Steve Taylor of Leeds Beckett University. In some ways, the trope is correct – environmental disruption appears to have an impact on violence, according to research cited by Taylor.

Fisher suggests this desensitization to cruelty by coopting it as “real” or “natural” plays a role in capitalist realism by justifying the individualistic, dog-eat-dog nature of capitalism as a natural human state, instead of an artificially created one.

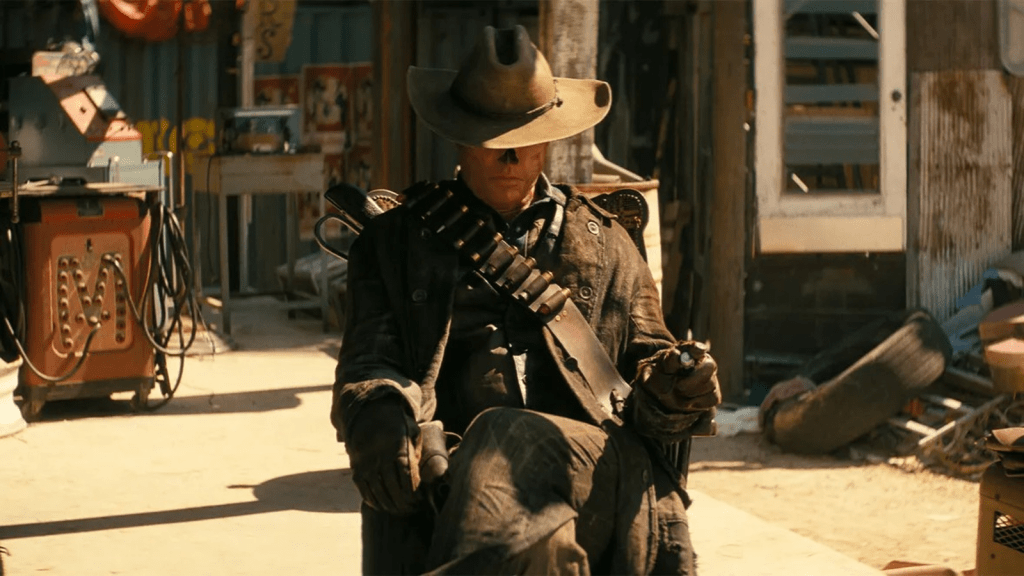

The character of the Ghoul—the ruthless bounty hunter that Cooper becomes, scarred by radiation and kept alive by a concoction of drugs—is a fantastic exploration of this theme.

Before the war, he played a cowboy on TV and had to be forced by studio executives to go along with a more brutal scene in which he shoots the villain dead. Now, as the Ghoul, he has come to embody both the aesthetics and the psychology of that stone cold cowboy character – life imitates art. His pre-War movie character’s famous line before murdering the villain – “feo, fuerte, y formal”– foreshadows this transformation into the “ugly, strong, and dignified” character of the Ghoul.

In his interactions with the escaped vault-dweller Lucy McLean, the Ghoul manifests what Fisher calls “a kind of machismo of demythologization.” He seems to take great pleasure in making the staunchly altruistic Lucy suffer while dragging her through the desert (to ultimately try to sell her organs), mocking her belief in “the golden rule.”

He even appears to take a kind of paternal pride in her when she bites off his finger during an escape attempt. “There you are, you little killer,” he says, confirming his own cynicism in human nature, before cutting off her finger to replace his own.

According to Fisher, fear and cynicism are the predominate affects in late capitalism, and a state of permanent structural instability fosters “stagnation and conservatism”—two words that describe Fallout’s wasteland well.

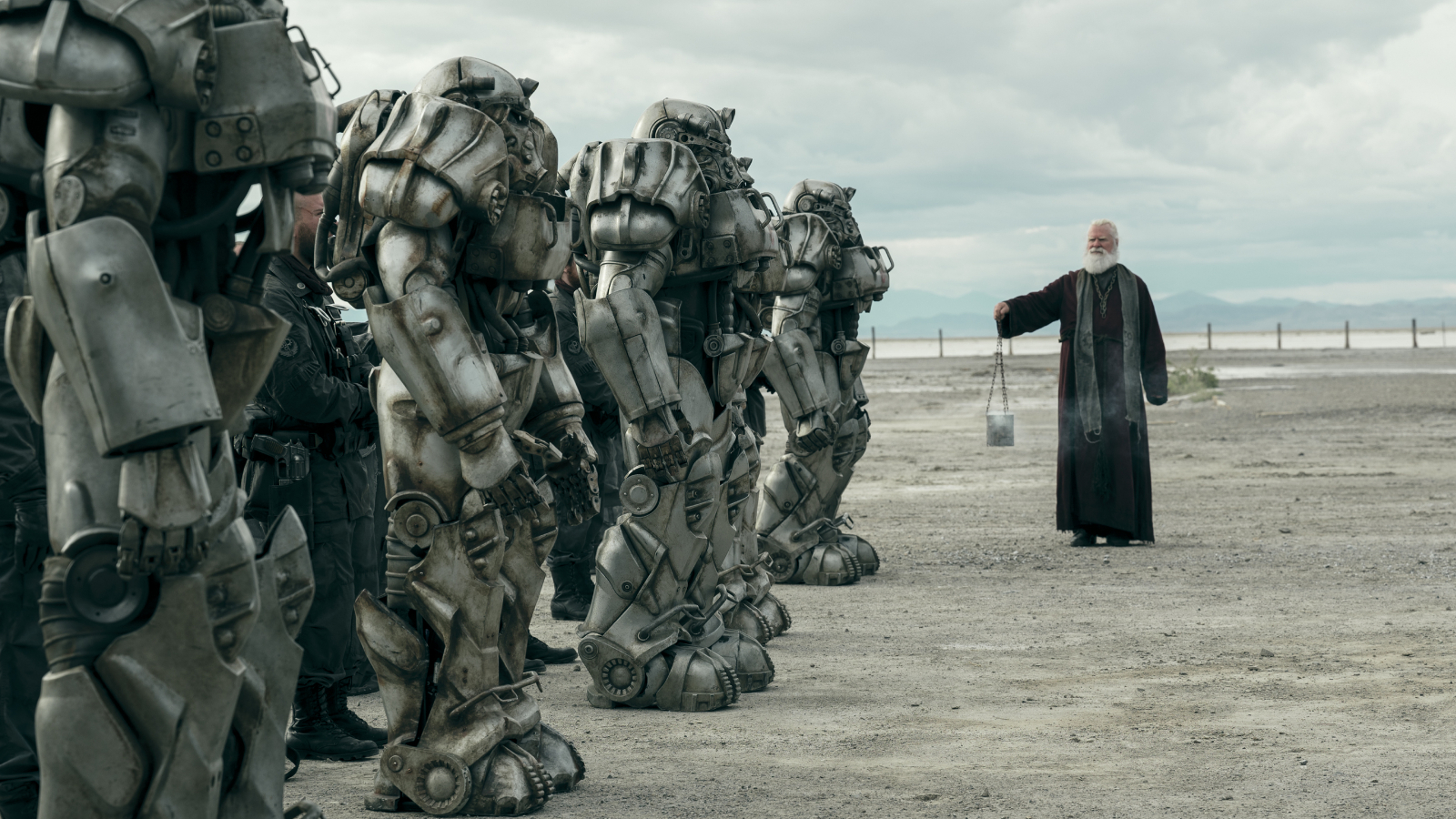

The Ghoul is not the only character adopting the aesthetics of the past in the face of instability. Another point-of-view character in the show, Maximus, introduces us to the Brotherhood of Steel, a quasi-religious paramilitary order that aims to preserve and control pre-War technology. The Brotherhood is incapable of producing anything new, only picking through the debris of the past. Its leaders wear the garb of monks and preach the Codex to its all-male aspirants.

Through Moldaver, the show introduces us to another major faction in Fallout: the New California Republic. The show does not dive too deep into what the NCR actually involved before it was decimated by the bombing of Shady Sands, but the faction is implied to be a restoration of pre-War society, a kind of idealized American republic. Fisher notes that the term “restoration” is frequently associated with neoliberalism. Players of the game will know the NCR is not exactly a good guy – it takes on the imperialist project of the U.S. it is trying to revive.

The mysterious Enclave is yet another backwards-thinking paramilitary faction that plays a small role in the show, but a larger role in the games. According to the game lore, the Enclave is a continuation of the U.S. government “deep state” comprising high-ranking political, military, and corporate figures. Its motto appears to be “God Bless America,” and it aims to cleanse “mutants” from the world and return power to “humanity.”

“A culture that is merely preserved is no culture at all,” Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism. The great irony is that it is exactly the capitalist imperialist society of the past that led to this nuclear holocaust in the first place, and trying to recreate those conditions seems incredibly illogical. Yet, the characters cannot imagine any other way—this is the endpoint of capitalist realism, its infiltration of the psyche.

As our protagonist Lucy makes her way across the wasteland, she not only encounters the physical rubble but also this ideological rubble of the past. Physically, the surface-dwellers live in the rotting corpse of the past—houses filling with sand, hollow airplanes, shipping containers, and shacks assembled from the debris of bombed out cities. Even skeletons remain unburied.

Haunted by the lost futures surrounding them, is it any surprise many wastelanders look to the past, find themselves trapped by it? As Fisher notes, “[i]t wouldn’t be surprising if profound social and economic instability resulted in a craving for familiar cultural forms,” and this seems to be the case for the factions the wasteland, just as it is in our current society.

Nietzsche warned that an “oversaturation of an age with history” leads to paralysis. In our world, as described by Fisher, late capitalism “breed[s] conformity and the cult of minimal variation, the turning out of products which very closely resemble those that are already successful.” It is by nature retrospective instead of forward thinking.

Eventually, this leads to what Fisher calls a “cancellation of the future”—this is apparent in our media landscape dominated by nostalgia. There are no new movies, only movies based on previously successful franchises. There are no new fashion styles, only regurgitated trends from the 90s and early 00’s. There is no new music, only revivals of 20th century sounds. There are endless critiques of capitalism but no proposals for any viable alternative.

We are surrounded by our own cultural wasteland, cluttered with aesthetic detritus from the past, removed from its original context and repackaged, reiterated, and regurgitated. There is a vague sense the world has already ended – there is nothing new to come.

The Fallout show itself is an example of this regurgitation—it is not new. It is a TV show based on a successful video game franchise with a safely established fanbase.

One could see the Fallout show as a critique of capitalist realism, given that its villain is a Big Bad Corporation and the show appears to criticize the anticommunist sentiments of the 1960s. However, it may fall into the trap of “interpassivity” identified by Robert Pfaller: the show itself performs anticapitalism for the viewer, allowing us to consume it without guilt and replacing the impulse to act against capitalism with passive consumption of anti-capitalist material.

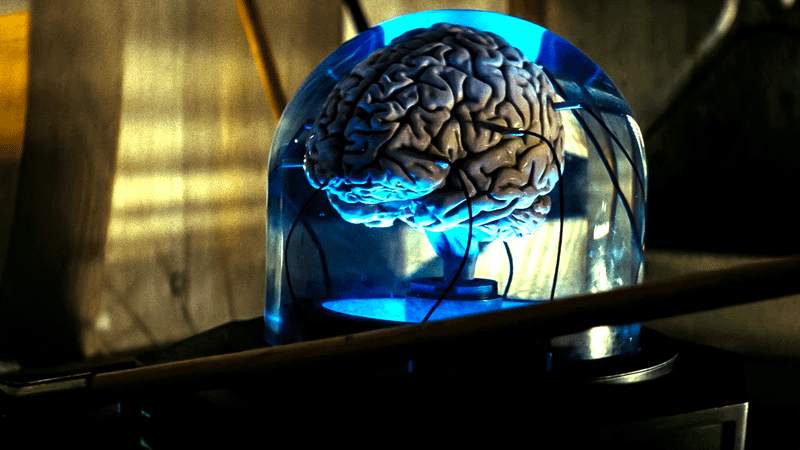

The show could actually be seen as making a case for capitalist realism. Vault-Tec’s fantasy of capital surviving the apocalypse becomes a reality, after all. Its managers survive in cryosleep to emerge and restart the company. “The future of humanity comes down to one word: management,” proclaims the disembodied brain of Bud Askins to Norm McLean when he discovers the cryochambers in Vault 31.

Even the surface-dwellers recreate a crude market system using useless Nuka-Cola bottlecaps as currency. The show constantly depicts mindless wastelanders enacting cartoonishly lurid violence upon each other, confirming a cynical few of human nature and encouraging a desensitization to cruelty that capitalist realism demands.

At first, I fully expected the show to lean into this cynical, individualistic, survival-of-the-fittest theme that Vault-Tec itself championed in the war room scene – applying the spirit of competition to ensure only the most suitable vault products survive.

However, the character of Lucy herself counters that grim assessment. As she leaves the shattered utopia of Vault 33 to find her kidnapped father in the wasteland, the show sets us up to expect the obvious character arch: wide-eyed Mary Sue gets beaten down by “the real world” and becomes a stone-cold badass.

But this isn’t what happens. Although almost everyone she meets tries to kill her, she always tries to do the right thing – the narrative resists punishing her for her moral compass or turning her into a mindless killer.

She has an especially poignant scene with the Ghoul in episode four. After she escapes the Super Duper Mart where Snip Snip the robot attempted to harvest her organs, Lucy emerges to find her tormentor, the Ghoul, collapsed on the ground. A more cynical narrative might have Lucy shoot the Ghoul or leave him to go feral, sealing her transformation from a goody-two-shoes into a desensitized, violent wastelander. Instead, she pauses to drop a handful of life-saving vials by his hand.

“I may end up looking like you, but I’ll never be like you,” she says. “Golden rule, motherfucker.” Similarly, her love for Maximus opens his mind to ways of life outside the confines of the Brotherhood.

The show ends with Lucy and the Ghoul joining forces to find out who’s really pulling the strings in the wasteland. Lucy’s act of altruism appears to have reminded the Ghoul of his true self – the Cooper that favored mercy over judgment, loved his family, and stood up for his ideals even when it meant the end of his marriage.

But what will they find at the center of this conspiracy? And will anyone be able to create a new way of life in this California hellscape? I don’t really expect a show produced by Amazon Prime to give me a blueprint for a viable post-capitalist society, but I am very curious where the writers go with the source material of Fallout, which is known for its philosophical richness and complex moral choices.

[Images used under fair use, courtesy of Prime Video]

Nicole Kurlich is a poet, freelance editor, and wannabe philosophy student who is probably unqualified to write about anything, but does so anyway. She lives in Chicago with her two cats, Toast and Jelly.

Leave a comment